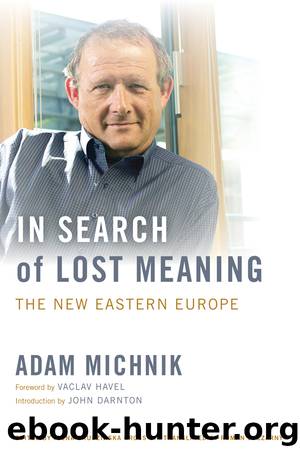

In Search of Lost Meaning by Adam Michnik

Author:Adam Michnik

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780520949478

Publisher: University of California Press

Published: 2012-01-23T00:00:00+00:00

VI

The accusations of the émigrés concealed despair, the child of defeat, and the despair of the poet Jan LechoÅ when he wrote his shocking poem about Reytan and then hurled accusations and abuse at MiÅosz. Nonetheless, in the shade of that despair, the spirit of the gutter was blooming, fed by the work of despicable bootlickers who sought the favor of the émigré notables and sent the American authorities reports denouncing MiÅosz as a Soviet agent. Behind the accusations in Poland stood the fury that is directed against a writer who has cast off his chains. After all, that writer, as the Communists believed, was already their property; he was a diplomat who had abandoned his mission. He had simply betrayed us. He had betrayed Poland, the revolution, and the literary establishment.

In his poem about the suicide of the poet Tadeusz Borowski, MiÅosz wrote: âBorowski has betrayed. He has escaped where he could. / Ahead, he saw the eastern commissaries, / Behind, the Polish reactionaries.â MiÅosz did not betray anybody or anythingâMiÅosz escaped. Francesco Guicciardini, Machiavelliâs friend, used to say that there is only one way to deal with a tyrant, just as there is only one way to deal with the plague: take to your heels and run, as far away as possible.

Obviously, the Communists couldnât understand any of that; a tyrant, for them, was the Spirit of History, the Inevitable Necessity, and the Benefactor of Mankind. They felt they were the soldiers of the revolution, drivers of the engine of history, and engineers of the human soul. In other words, they were blind fanatics; narrow mental horizons (the narrowness understood as selfless devotion to an idea), ruthlessness and cruelty in human relations, and the inability to perceive reality realisticallyâthese made up the character of a tough Bolshevik. It was these people who saw MiÅosz as betraying the revolution. âThere are no honest traitors!â they repeatedâbut there was also no possibility of an intellectual discussion with a traitor, because betrayal is not an intellectual notion. The Communists, trapped by the limits of their own discourse, reached for the vocabulary of slander and the smear campaign. The writers close to MiÅosz were quite different. We have quoted Iwaszkiewicz and SÅonimski, because their guilt was so instructive that we could not omit their voices. However, their actions and attitudes were motivated not only by fear of the totalitarian regime but also by a conviction that MiÅosz had some sort of unwritten commitment, under which even here, in the old country, even if the price was high, one had to âsave what could be saved.â And it was in that particular sense that they felt betrayed. MiÅosz seemed to have shared that point of view, and possibly that is why he clarified his motives so extensively.

Let us repeat: MiÅoszâs decision was judged in a variety of ways. But the behavior of the writers who took part in the smear campaign against him can only be described as shameful. The insinuations that MiÅosz

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| General | Channel Islands |

| England | Northern Ireland |

| Scotland | Wales |

Room 212 by Kate Stewart(5119)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4814)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(4780)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4354)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4211)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4109)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(4001)

Say Nothing by Patrick Radden Keefe(3984)

I'll Give You the Sun by Jandy Nelson(3446)

Shadow of Night by Deborah Harkness(3367)

Hitler's Monsters by Eric Kurlander(3341)

Mary, Queen of Scots, and the Murder of Lord Darnley by Alison Weir(3210)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(3203)

Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell(3171)

Darkest Hour by Anthony McCarten(3129)

Margaret Thatcher: The Autobiography by Thatcher Margaret(3081)

Book of Life by Deborah Harkness(2938)

Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine by Anne Applebaum(2932)

The One Memory of Flora Banks by Emily Barr(2863)